Under the banner of #NormaalAcademischPeil ('normal academic standard'), Dutch universities have started a coalition to demand a structural increase of €1.1 billion in government funding. This action is broadly supported by the academic community, and I'm also sympathetic to it myself. However, I feel that the action is too narrowly aimed at defending the interests of universities, without properly considering the role of universities in society at large.

The problems at Dutch universities are very real and multifaceted; they touch upon things such as the pervasiveness of temporary contracts, hypercompetion for grant funding, and the high salaries of full professors.

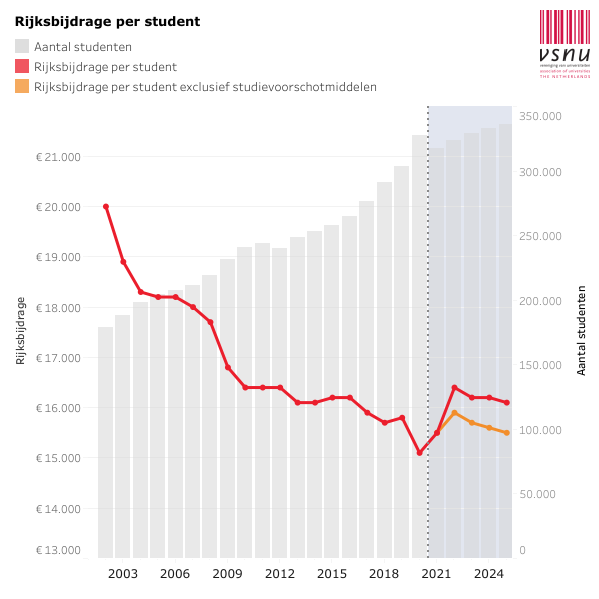

However, the coalition has chosen to focus on the figure below as illustrating The Problem. And it's this figure that I will also focus on in this post, because I believe that it reflects a complex reality that is very different from the simplified picture painted by the coalition.

'The Problem' is that the number of students who attend a Dutch university has almost doubled over the past twenty years (the grey bars; from about 175,000 to 300,000). In that same period, government funding per student has decreased by 25% (the red line; from about €20k per student to about €15k). In other words, universities have more budget in total, but less budget per student.

Based on this, the coalition correctly points out that the quality of university education has suffered. In practice, this means that many lectures have become mass productions. (I have lectured for a first-year cohort of almost 800 students.) More generally, students receive less personal feedback and attention now, as compared to twenty years ago.

All of this is true, and it is problematic. But at the same time it is only one side of the story. Because two crucial pieces of information are missing from this figure and from the debate surrounding it. Namely: Where do these additional students come from? And how much was invested in their education twenty years ago (when they did not attend university)?

The growing student numbers are likely due to a combination of factors, but the main factor is likely that students who twenty years ago would attend a hogeschool 1 (or a similar school) are now more likely to attend university. I don't have exact numbers about government funding per student at a hogeschool. But I suspect that it is substantially lower than that for university students, in part (but likely not only) because a hogeschool bachelor's degree takes three years, whereas most university students obtain a master's degree after four (regular master) or five (research master) years. And now that more students are attending university, funding per university student naturally declines to a level that is closer to that for hogeschool students.

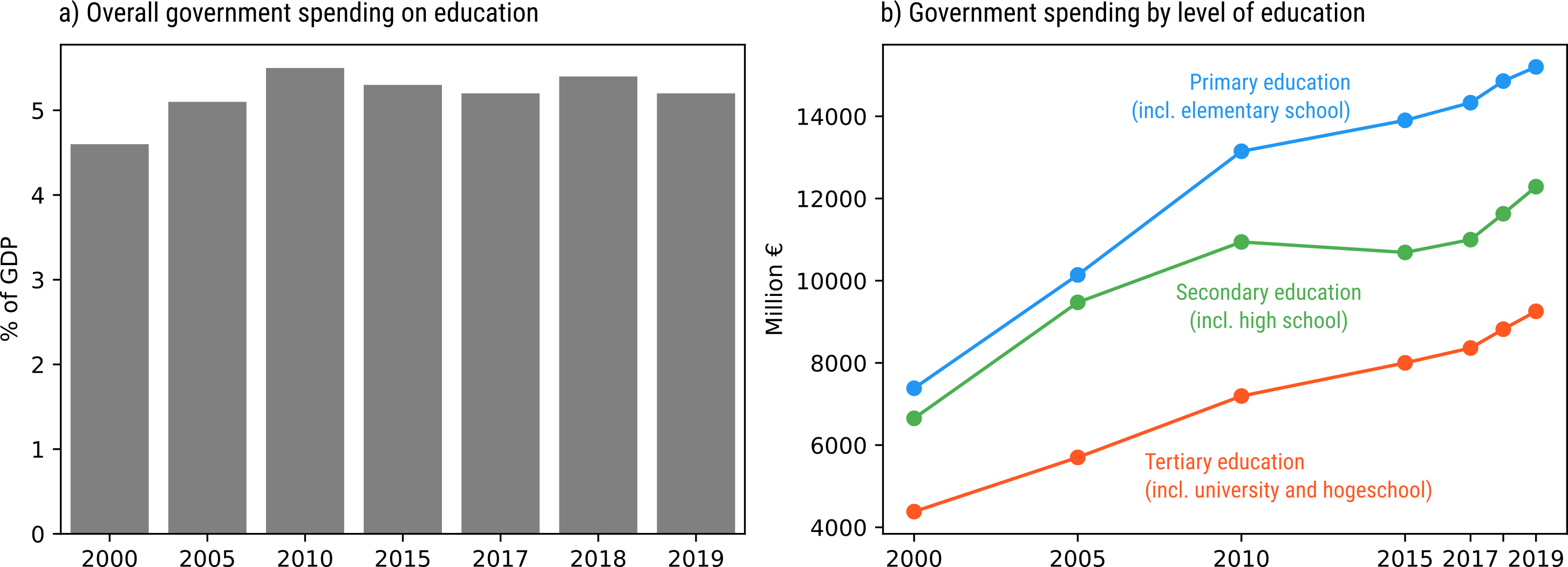

This interpretation seems to be supported by data from the Dutch bureau of statistics, which shows a few imporant points: Goverment funding for education expressed as a percentage of the gross domestic product (GDP) has slightly increased from 4.6% in 2000 to 5.2% in 2019 (see left panel in the figure below). Within education (expressed as €, so because of inflation all budgets increase), the budget for tertiary education (orange line; includes universities and hogescholen) has increased by 211% in that same period, whereas the budget for secondary education (green line; includes high schools) has increased by only 200%, and the budget for primary education (blue line; includes elementary schools) by only 184% (see right panel in the figure below). In other words, over the past twenty years, the Dutch government has slightly increased its funding for education, and a slightly larger slice of this pie is going to tertiary education, which includes universities.

So what does 'The Problem' really reflect? It seems to reflect an increase in the equality of education: Whereas university-level education used to be reserved for a select group of students (mostly from higher socio-economic classes), the past twenty years have seen a tendency for university-level education to be open to a larger group of students (presumably also from a wider range of socio-economic classes).

Is this good or bad? It's neither. On the one hand, the quality of university education has suffered because of the reduced budget per student; on the other hand, more people benefit from university education. Importantly, there is no evidence that education as a whole is underfunded, or at least not more so than twenty years ago. Resources are just being distributed differently.

A nuanced discussion should take all of the above points into consideration, and focus on the role that universities should play in society. Do we, as society, want universities to remain an elite bastion of a select group of highly educated individuals? In that case, the number of students should go back to being severely limited. Or do we want as many people as possible to benefit from the highest level of education, even though this means that the quality of education will suffer (but still be good)? In that case, we're on the right track. There can be legitimate differences of opinion about these matters. But choices have to be made: Given relatively constant government funding for education, it's either the one or the other.

Or is it? As a society, we can also choose a truly progressive educational system with increased funding across the board, from elementary schools to universities. But this will cost money, and this money will have to come from increased taxes, and these increased taxes will (or should) weigh predominantly on the shoulders of the richest members of society, which includes the same professors who are now advocating for increased government funding for universities. And while they are keen to procure a larger slice of the pie for themselves (and, to be fair, for their lesser-paid colleagues), it is doubtful whether they are equally keen to contribute to increasing the size of the pie for everyone.

In a context of limited resources, the question of whether universities are underfunded is complex and requires a careful deliberation of how resources should be distributed fairly and effectively. And, unlike the #NormaalAcademischPeil coalition suggests, the answer is currently not a clear-cut yes.

-

A hogeschool, sometimes translated as university of applied sciences, is the second level of tertiary education in the Netherlands. They are not considered universities in the sense of the #NationalAcademischPeil coalition. ↩