Een Wereld vol Denkers (A World of Thinkers) has been out for a little more than a week now. It’s a Dutch-language popular-science book. My first! There’s much to say about the book itself. I’m very excited about it! But here I want to focus on the journey, rather than the content. I set out to write a book that I would want to read. Here’s why and how this book came to be.

Let’s start with the why: I enjoy reading (popular) science books myself. From Oliver Sacks to Zoë Schlanger to Leonard Susskind: a thin slice through the S-section of a very long bookshelf that spans most of the length of my living room. I love the feeling of being immersed in a universe of ideas. And just as every football fan dreams of becoming a professional football player, and just as every music lover dreams of becoming a rock star, I dream of becoming a writer. (I dreamt of becoming all of these things at some point.)

I also have more earthly motivations to write. A promise casually made in the public-outreach section of an unexpectedly funded grant proposal. Vanity, certainly. Money was not a factor at all, as I will explain later. But my main motivation was the activity itself. The satisfaction that I get from writing about interesting stuff. Admittedly a pretty egocentric motivation.

Of course I get most satisfaction from writing about stuff that I would want to read about. Is it a good idea to write with some version of yourself in mind as the audience? Marketing people would surely tell you no, but I’m not sure it is such a bad starting point. At least you don’t have to guess what your audience will or will not like! Besides, at least in my case, my tastes are hardly unique. I enjoy pretty much any popular Netflix show, having even gone as low as finishing all four seasons of Stranger Things. I listen to mainstream music, or at least music that was mainstream twenty years ago. Which is to say: if I like a book, there’s a good chance that other people will like it too. Or at least I hope so.

But it’s not just about what I want to write. It’s also about what I am able to write. I’m a cognitive neuroscientist with a pretty limited domain of expertise. My research group tries to understand how small changes in the size of the eyes’ pupils shape human visual perception. I could write an entire book about this topic. But I wouldn’t want to read this book. It would be too narrow, better suited for a review article. On the other hand, if I stray too far from what I know, I would no longer be a reliable guide—science writing requires knowledge. So I needed to find a sweet spot. A topic that I felt comfortable writing about, but that would still be broad enough to appeal to a general audience.

The sweet spot that I initially had in mind was perception in non-human animals. But just as this idea was coagulating in my mind, about two years ago, two books on this exact topic appeared: Sentient by Jackie Higgins and An Immense World by Ed Yong. Excellent books by two heavy hitters. I was afraid that another book on the same topic would simply pass by unnoticed. Certainly coming from a name unknown to the general public.

Meanwhile, the AI revolution was in full swing. Lots of books were published about AI. Most of these weren’t books that I would like to read. Some were alarmist works, written by activists with a burning desire to warn of impending doom resulting from catastrophic environmental and societal damage; others were futurist works, written by evangelists preaching the gospel of AI’s unstoppability and near-limitless potential.

There didn’t seem to be many science writers who looked at AI through the lens of psychology, which is after all the lens you should be looking through if you consider AI to be a form of thought! I had found my angle. Part of it, at least. The idea was still incomplete.

On an impulse and possibly motivated by a Kanye-Westesque illusion of grandeur, I decided to write about everything! Not just AI, but all the different ways of being and thinking around us: humans, animals, plants, and AI. I would take psychological concepts and theories, as I used to teach them in Introduction to Psychology. And I would use these to consider the many ways of being and thinking so different from our own. Buttercup flowers track the movement of the sun across the sky—do they perceive the sun? Bumblebees work for the survival of the nest, rather than their own—do they still fear death? AI chatbots seem pretty smart—what do theories of human intelligence have to say about that?

This probably sounds like an eclectic selection of topics, and in a sense it is. But it’s a carefully curated selection. I wanted to catalogue the different forms of thought around us. And from there attempt to systematically understand both the similarities and differences in all of this diversity. I wanted to embrace the irreducible complexity of the world around us—which means staying clear of grand sweeping theories that ultimately explain very little!—while still offering the reader a narrative thread to structure their thoughts as well as my own!

I had lots of ideas. But I hadn’t written anything yet. And I didn’t have a publisher either.

Stefan van der Stigchel had already published a number of science books, including How Attention Works and Concentration. Both of these were initially published in Dutch and later translated to English. Stefan is my academic older brother. We both obtained our PhD with Jan Theeuwes. Every once in a while I turn to Stefan for advice. Shall I put you in touch with my publisher? he asked when I presented my ideas to him. Yes please, I replied. His publisher, Maven, mainly publishes popular psychology, including a lot of self-help books. My book would clearly be an outlier in both style and topic. But they were nevertheless enthusiastic, which gave me an enormous confidence boost.

I met with Maven a few times in their Amsterdam office. They gave me good feedback. I had initially planned to write the book from the perspective of a student following a university course. Each chapter would be a lecture, and the nonfiction parts would blend with a simple fictional story line focused on the main character. A bit like Sophie’s World, the famous Norwegian book that blends philosophy with fiction. But Maven cautioned me against this. The topic was already very broad, they said, and adding a layer of fiction on top would become… too much. I reluctantly conceded that they were right, and dropped my fanciful idea in favor of a more traditional format. I was still going to enliven the book with personal anecdotes and literary references. But the focus would be squarely on the science.

A few months later, I received a major setback. Despite their initial enthusiasm, Maven had decided not to move forward with my book. They had read a draft of the first few chapters, and felt that it was not a good fit for them. As I already mentioned, they had a point, because indeed what I had in mind was very different from their usual repertoire. But they had already known this from the start, and so I suspected the real reason was that they were worried that the book wouldn’t sell, perhaps (oh no!) because they were disappointed by my writing.

Fortunately, this setback was only temporary. Maven offered to put me in touch with another publisher, Uitgeverij Balans, another premier nonfiction publisher in The Netherlands. Balans would be a much better fit for me, they said. I initially took their offer as just a gentle way to let me down. (“It’s not you, it’s me.”) Maybe in part it was, but they did pass on my manuscript with a glowing recommendation. This turned out to be a very good thing. I met with Balans in their even more beautiful Amsterdam office—what I wouldn't give to work there!—and they offered me a contract on the spot.

I did not sign immediately, though, among other reasons because a new possibility had appeared on the horizon. A friend and colleague had put me in touch with a successful international nonfiction author, who had in turn put me in touch with someone who might be helpful in finding an American publisher. Here I suddenly had—or thought I had—a real chance to reach a world-wide audience! Something that would never happen with a Dutch publisher, not even if my book would be translated. So I took a detour to explore this possibility.

It quickly became clear to me just how wildly different American and Dutch publishing cultures are. In the Netherlands, authors are typically in direct contact with publishers. The whole process is fairly transparent, even if the outcome is often rejection and disappointment. I learned that in the US, and more generally in the English-speaking world, authors are rarely in direct contact with publishers. Instead, agents negotiate on their behalf. I initially thought that my contact was such an agent. I don’t see why I would need an agent, though perhaps I am too unfamiliar with the process to see their value; but in any case I was happy to play along. However, it turned out that my contact was not in fact an agent, but rather someone who offered training to aspiring authors on how to find an agent. Maybe I’m cynical, but I felt that this ‘training’ amounted to buying access to this person’s contact list. Throughout the process, I got a strong sense of gatekeeping and self-importance. I decided this was not what I wanted, and aborted the detour. Very happily, I decided to sign with Balans.

Book contracts in the Netherlands are standardized through a collective labor agreement, which essentially means that authors and writers have collectively agreed on the basic terms. Royalty percentages aren’t fixed, but as far as I can tell an author typically receives about two euros per book sold. This sounds decent, but there are a few things to consider before planning a writing career followed by an early retirement. Especially if you’re an academic. First, Dutch universities do not—and for good reason—simply allow their staff to make money on a personal title for activities that are linked to the university. This clearly applies to my book, if only because the back flap states prominently that I am a researcher at the University of Groningen. The upshot of this is that in order to receive royalties I would need to contact the University’s Human Resources (HR) office, and come to some kind of agreement about how to divide the royalties between the university and myself. People are cagey about these kinds of arrangements, but as far as I can tell 50/50 seems to be common. I would then be left with about a euro per book sold before taxes, and only about fifty cents after.

In The Netherlands, a book is already considered a national bestseller when it sells around 10,000 copies. But let’s face it—even if my book becomes a success in its genre (which seems to be happening!), it will never be a national bestseller. It has neither the famous author nor the clear human-interest angle required for such numbers. Given that I would likely not make a lot of money anyway, I decided to opt out of receiving royalties altogether. Instead, I added a clause to the contract stating that, up to a certain amount, royalties are used for paid marketing of the book. Perhaps this will boost sales a little. And in any case I would not have to suffer through a meeting with HR, which is also worth a lot.

One of the things that I appreciated in working with Balans, was their openness to my suggestions. I had a clear picture of what I wanted the book to look like. Or rather, I had a clear ultra-high-definition photograph. I wanted each chapter to open with a beautiful illustration, such as the one above, by my friend Theo Danes. I wanted decorative symbols to indicate where specific chapter sections start and end. I wanted a light sans-serif font for the headings. I wanted one of the fern leaves on the cover to become an octopus tentacle that reaches for the little bird. I micromanaged, in other words. (Sue me. It’s my book!)

The publisher seemed surprised that an author would have such strong feelings about layout and typesetting. Mostly they obliged, and even seemed appreciative of the attention to detail. On a few occasions, they stood their ground. For example, they declined the book cover that I had designed myself. I’m happy they did, because the actual cover turned out beautiful. They insisted on the subtitle “Op zoek naar het bewustzijn van mens, dier en plant (en misschien zelfs AI)”, which loosely translates to “The search for consciousness in humans, animals, and plants (and maybe even AI)”. The parenthetical clause and the use of “maybe” felt clunky to me, and I still don’t like it. But I compromised, because compromise goes both ways. I think both parties were satisfied with the outcome.

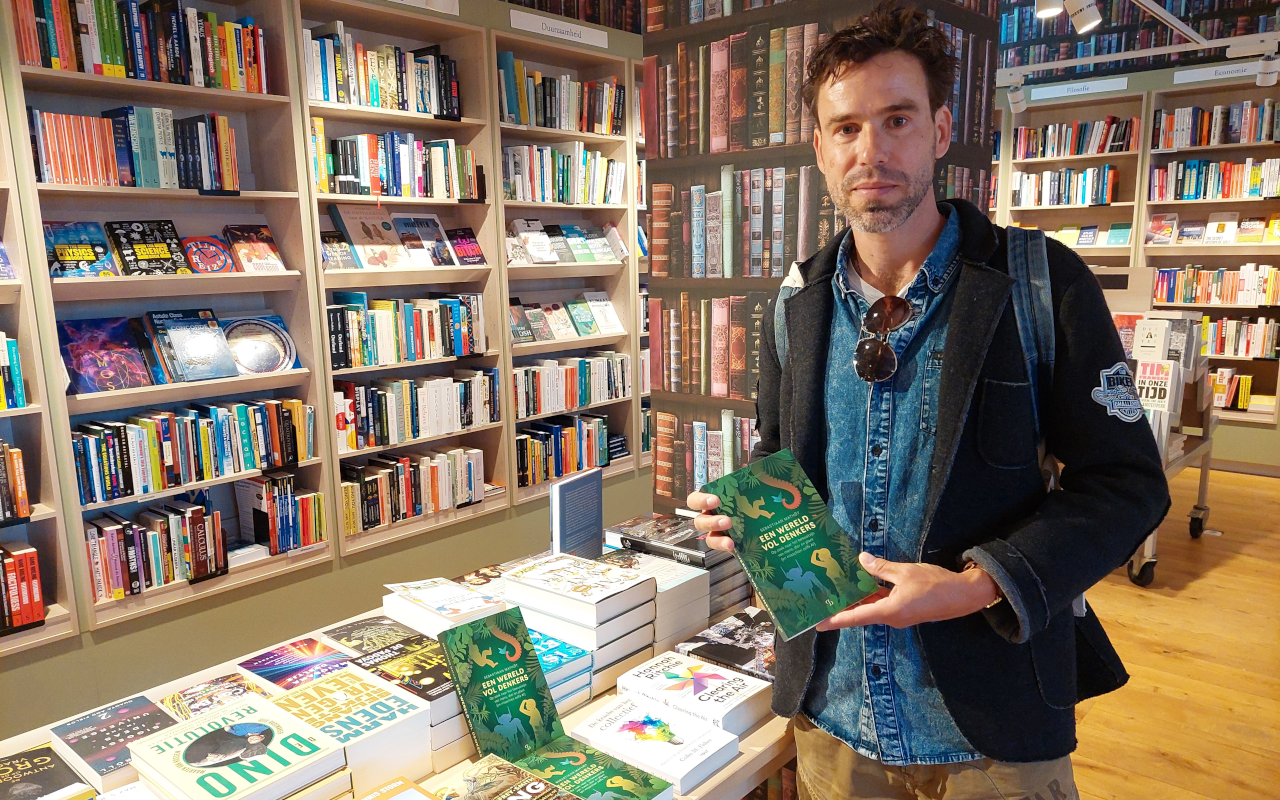

When the book was finally released a little more than a week ago now, I had no idea what to expect. Would it be generally available in all major bookstores? (Yes!) If so, would it be prominently displayed on tables, or vanish into the obscurity of the shelves? (Mostly on tables, but usually not among the bestseller selection.) Would I get a lot of responses from readers? (Only a handful so far.) Would I get invited to the national book gala? (Still hopeful…) But what continues to surprise me most is: the book is out there and I’m proud of it!

Finally, to all the people who helped me—Lennart, Lotje, Theo, Stefan, Surya, and many others—thank you! You helped me write the book that I wanted to read.